“We are ruled, and resign to let ourselves be ruled, by our own weakness and by the prejudices of those who, more guilty or more frustrated than ourselves, need to exercise great power. We let them. And we excuse our cowardice by letting ourselves be driven to violence under ‘obedience’ to tyrants. Thus, we think ourselves noble, dutiful, and brave. there is no truth in this. It is a betrayal of God, of humanity, and of our own selves. Auschwitz was built and managed by dutiful, obedient men who loved their country, and who proved to themselves they were good citizens by hating their country’s enemies.”

– Thomas Merton, Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, pg. 53

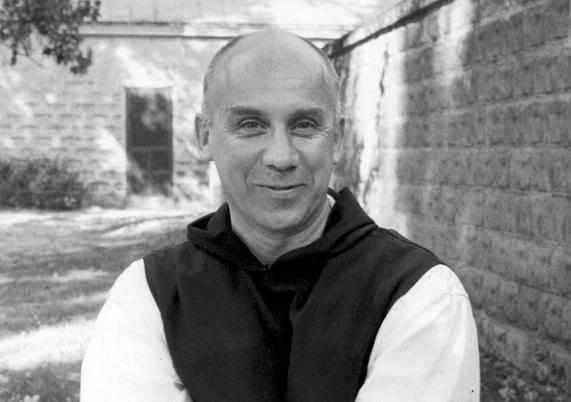

I used to shelve Thomas Merton’s books in a New Jersey Borders Books and Music. I frequently wondered if he was some kind of heretic. He appeared to be a Catholic Monk, but a bunch of eastern religion authors really loved him. One even called him a Zen. His posture on all of his book covers resembled eastern writers, and some of his books specifically addressed eastern religion.

**RED FLAGS**

**RED FLAGS**

If I could have slapped a “Read with Discernment” sticker on his books, I would have considered it. After all, I was the keeper of the religion and philosophy sections. I also shelved the slightly zany metaphysics and the steamy erotica books—both categories could have used larger stickers on them in general. I still carried some of my personal grudges against the Catholic Church during that season of life—one my Catholic friends reminds me that I was raised “IRISH CATHOLIC.”

As I hit my peak of evangelical fervor during those years of attending seminary, shelving sometimes questionable books, and vigorously encouraging everyone to avoid the Left Behind series, a Catholic with connections in eastern religion like Merton appeared just about as far out of bounds as you could get from my perspective.

In the years that followed, I had a relatively standard faith melt down and clung to some semblance of Christianity primarily through praying the scriptures with the Divine Hours. When I no longer felt like I had much left of my faith to defend, I started reading some Catholic authors. I had already read a little bit of Henrí Nouwen and Brennan Manning at an evangelical university, so I felt safe to start with them. Enough people in my circles recommended Richard Rohr, so I dove into his books as well. In each case I plowed through a stack of books by each author. I couldn’t help noticing just how frequently Nouwen and Rohr mentioned Thomas Merton.

Maybe it was time to give him a try?

Tucked away in my stacks of theology books, I found a Merton book that had survived several purges and moves since I picked it up in 2008 at the Northshire Bookstore in Manchester Vermont. It had been on a sale table presumably because it hadn’t sold well. The book, titled The Echoing Silence, is a collection of short excerpts from Thomas Merton on writing. At the time, I figured that even if he was influenced by eastern religion, he had written quite a few books that sold well. He probably knew a thing or two about writing. Also, the book was cheap and it had a very appealing picture on the cover of Merton’s writing desk—sold.

As it turned out, Merton repeatedly blew me away with his insights on writing, faith, and many other topics from the 1950’s and 60’s. I especially enjoyed reading his personal letters that offered “off the record” commentaries on racism and communism in America in the 1960’s. His letter to James Baldwin, a favorite author of mine, praised Baldwin’s perception and insights.

As I grew familiar with Merton’s faith in his own words, as opposed to my impressions of his book covers and the views of slippery-slope obsessed evangelical websites, I benefited from his artful prose that cut to the heart of weighty topics without mincing words.

I knew that I needed to follow up with some other Merton books. I plowed through Thoughts in Solitude, his compilation of the desert fathers, and the New Seeds of Contemplation. I had started the Seven Storey Mountain, but then the 2016 American election ruined that, as it will surely ruin a great many things in my country.

Facing the existential, moral, religious, and legal crises that such a presidency brings to America, I craved guidance from someone who had faced similar problems from the standpoint of having his feet firmly planted in the rich soil of contemplation without cramming his mind with the paranoia of social media or the bombast and speculation of the news channels. Merton faced growing fears about a very likely nuclear strike from the Soviet Union, paranoia about Communist infiltration of America, and growing tensions over racial injustice. In other words, his world had more than enough to worry about.

My Christmas list this year was basically just: “Merton books.” I’ve been working through Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, and it has offered a measure of comfort that one can be fully committed to ministering to the entire church while still taking strong stands for justice—including stands against the immoral actions of political parties.

Evangelicals have not historically hit it out of the park when it comes to pursuing justice in a non-partisan manner (although the Moral Monday movement and The Red Letter Christians are offering hope for a path forward). Even Billy Graham, an evangelical icon if there ever was one, finally softened his partisan political involvement after his friendship with Richard Nixon nearly ended his ministry altogether. In fact, Graham’s reputation was saved in part because a TIME magazine editor declined to publish his public endorsement of Nixon. Graham was deeply grateful for this and subsequently adopted a more hands-off approach to one political group or another.

In Merton I have found someone who was both hands-on in his approach to social justice and current events, while also maintaining compassion for all sides, keeping himself from being claimed by a particular political party.

I’ll be the first person to admit that over the last eight years of a Democratic president that I neglected to speak out against injustices and harmful policies until his final term. I want to find a way to reclaim a prophetic Christian voice in politics that works for God’s best for all people, even if that means having hard words at times for people who support certain politicians and policies.

When a politician votes to remove health coverage from millions of people who depend on it to stay alive, there isn’t a middle ground to stand on. One is either for death or life.

When a politician wants to gut laws that guarantee equality for oppressed minorities, one is either for justice of injustice. There is no polite way to accept the oppression of a person created in God’s image when such oppression denies that very status.

When a politician removes environmental protections that safeguard our water, air, and soil, then the world is either God’s good creation or just a meaningless pile of rubble and water that we can use however we please.

Merton wrote with sharp moral clarity about the misplaced paranoia of communism, our culture’s all too easy acceptance of mutual nuclear annihilation, the mind-numbing medication of entertainment, and the grievous moral failure of racism in America. He pushed his Catholic church to the limit, and he clearly opposed many Catholic leaders who all too easily embraced an oversimplified portrait of the fight against Communism. Of course, Merton also deftly dismantled the hollow atheism of the Soviet Union and its determination to offer order through a totalitarian regime.

As America enters a period where voting rights continue to be attacked, immigrants are hunted down, perpetual drone warfare rages on, propaganda drowns out the truth, and the threat of terrorism is called on trample the rights of others, the words and actions of a contemplative Christian who faced similar challenges in his own time has proven to be indispensable. Merton’s voice is hardly the only voice I’m seeking out, but my distance from the issues of his time offers a sharpened clarity into his perspective.

Christians (especially white Christians like myself) often say that they would have stood up for civil rights in the 1960’s. As Martin Luther King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail proves, many Christians urged King to be less disruptive in his useful of nonviolent protests and to wait for things to get better. I suspect that the current political situation may provide a similar test of just how much Christians today have embraced the Bible’s teachings that God desires his people to seek justice for those who are suffering:

Isaiah 58:2-3

“Yet day after day they seek me

and delight to know my ways,

as if they were a nation that practiced righteousness

and did not forsake the ordinance of their God;

they ask of me righteous judgments,

they delight to draw near to God.

“Why do we fast, but you do not see?

Why humble ourselves, but you do not notice?”

Look, you serve your own interest on your fast day,

and oppress all your workers.

Malachi 3:5

“I will be swift to bear witness against the sorcerers, against the adulterers, against those who swear falsely, against those who oppress the hired workers in their wages, the widow and the orphan, against those who thrust aside the alien, and do not fear me, says the Lord of hosts.”

We can disagree about which policies in our nation will best uphold these words from scripture, but ignoring them or violating with our laws are not an option if God’s Kingdom is our primary allegiance.

Today, I hear from a lot of Christians that we should be focused on only sharing the Gospel. Pastors and authors who make a living as speakers and writers are afraid to speak against injustice in America today lest they lose speaking engagements—and those who have spoken against the current administration have certainly lost speaking engagements. There are fractures in my own evangelical world between those who support our president and those who do not. If my career as a Christian author rests on lending even tacit support for such a man through my silence, then my faith is a flimsy, ramshackle thing that will soon collapse on itself.

As I think about the turmoil in my own evangelical subculture today, I imagine Thomas Merton writing at his neat little desk in his cabin. He encouraged civil rights leaders and artists. He built bridges across national boundaries with his fellow poets in Russia. He wrote about the failure of his Catholic Church to address the threat of nuclear warfare.

Merton may have lost some speaking engagements. His superiors may have censored him. But he was already sitting by himself in a secluded cabin in the woods outside of Louisville, Kentucky, occasionally instructing his fellow monks. To the eyes of the world, he had already lost. He was a zero, but then, that’s what he called himself. Rather than measuring the highs and lows of his influence, he committed himself to contemplation in isolation. From there he saw the issues of his day with a straightforward clarity that guided his writing and speaking. There was no cost/benefit analysis.

Merton sought the love of God and experienced divine union, calling others to this unity in love.

Merton saw the madness of his time and called it madness.

As I seek the words of Merton during this tumultuous time in my country’s history, I hope to become grounded in a similar love for all people that won’t back away from moral clarity. God knows we’ve tried to follow the advice of Christian leaders in megachurches, and that gave us a racist, xenophobic, pathological liar, demagogue as our president. Could a Catholic monk do much worse?

Read More about Contemplative Prayer…

After years of anxious, hard-working spirituality, I found peace with God by practicing contemplative prayer. I’ve written an introduction to this historic Christian practice titled:

Flee, Be Silent, Pray:

Ancient Prayers for Anxious Christians

On sale for $9.99 (Kindle)

Amazon | Herald Press | CBD